Propane’s unique position in the school bus market

One of the largest fleets traversing U.S. roadways takes kids to and from school each day.

About half-a-million school buses hit the road early every weekday morning, return to the bus yard, maybe make some mid-day runs for extracurricular activities or field trips and head out again in the afternoon to ferry students home.

About 5 percent of those buses run on propane, but in the coming years, that number is likely to expand significantly.

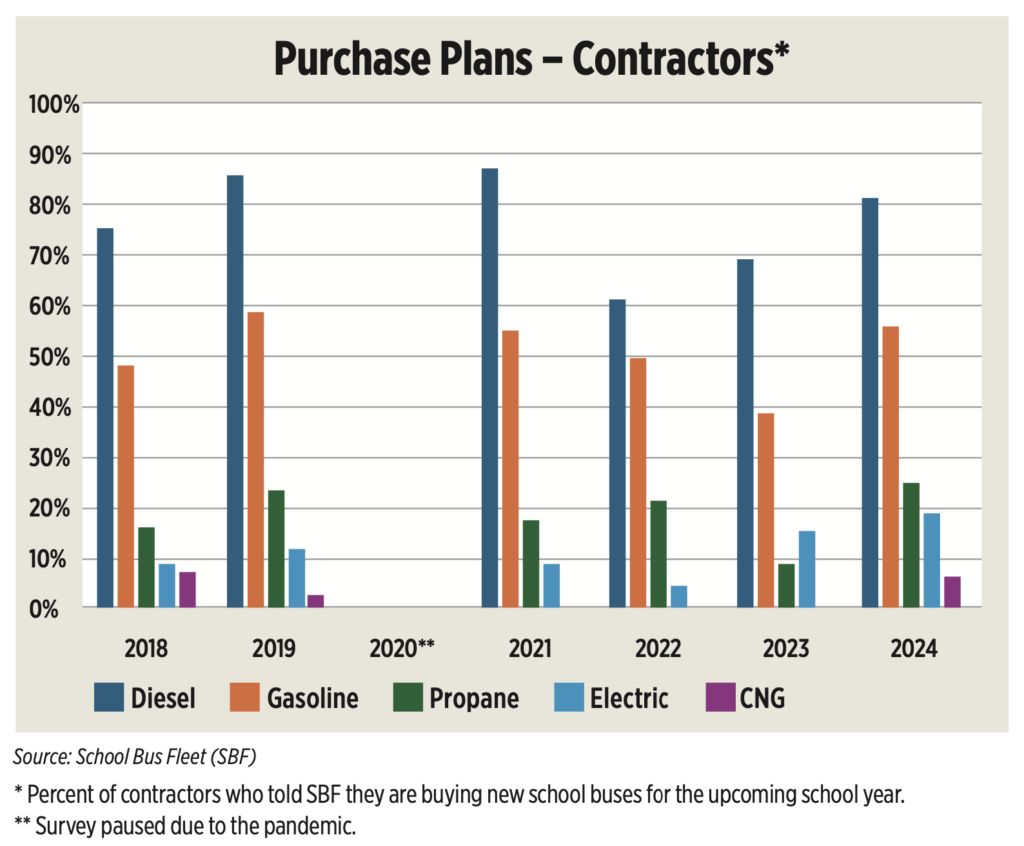

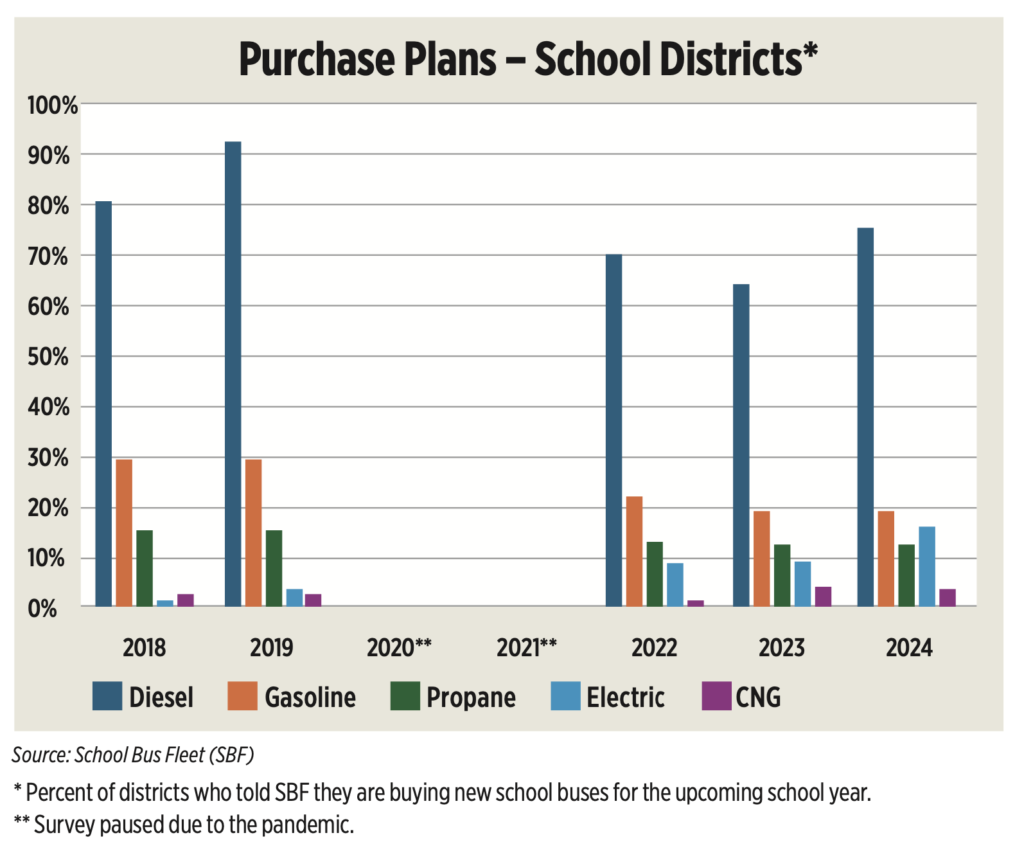

On one end of the fueling spectrum sits diesel, which takes the largest share of the school bus fueling market and has done so historically. On the other end, electric buses have captured a minuscule but growing share. Meanwhile, propane sits comfortably in the middle, even if it hasn’t grown by leaps and bounds.

With regulations tightening diesel emissions and the new presidential administration rolling back electric vehicle requirements and funding, propane is in a unique position to capture a bigger share of the market.

Rate of adoption

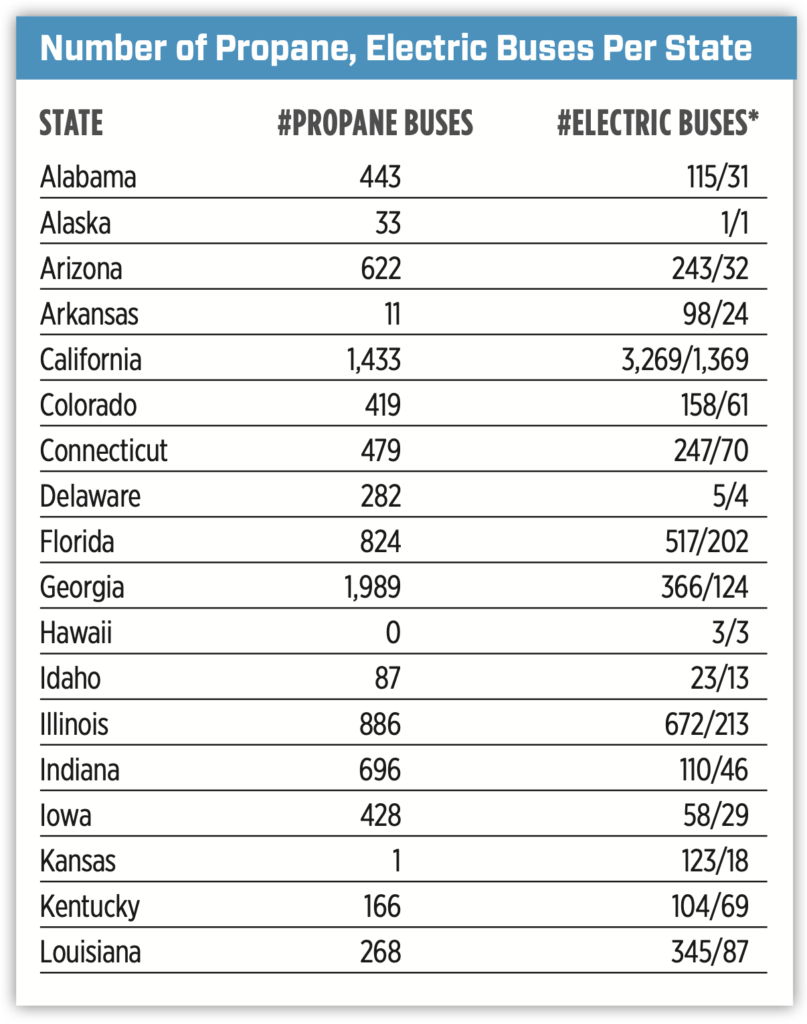

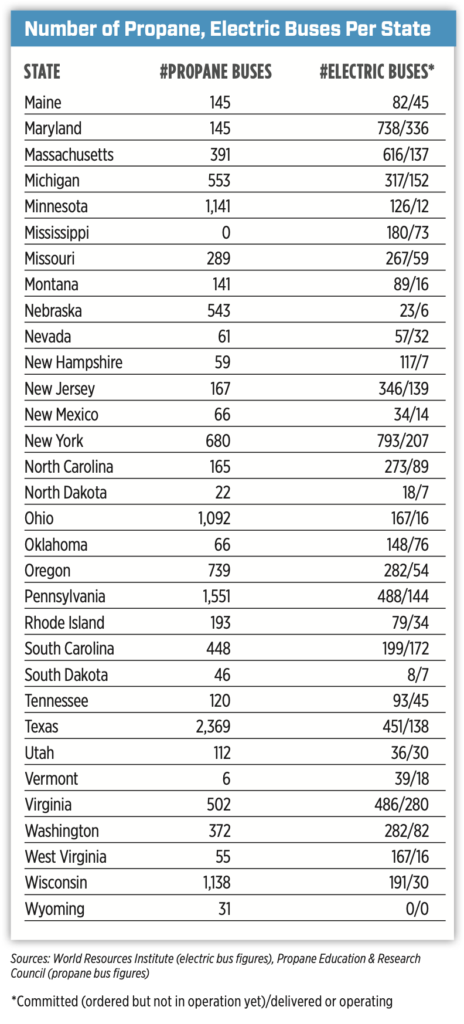

About 5,000 electric school buses are on the road in 49 U.S. states (Wyoming is the exception), as well as in Washington, D.C., and American Samoa, according to World Resources Institute (WRI). In addition, four territories and several tribal nations have committed to adding electric school buses to their fleets.

According to WRI, more than two-thirds of committed electric school buses in the United States were funded by the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean School Bus Program, which has distributed almost $3 billion to replace over 8,000 diesel school buses. (It is important to note that in January 2025, the Trump administration issued an executive order pausing the disbursement of funds through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021. This includes the Clean School Bus Program.)

Still, several states have passed legislation to mandate a transition to zero-emission school bus fleets, which could slightly boost the rate of adoption.

Although some Clean School Bus Program funding has gone to propane school buses, financial support for electric school buses has largely outpaced it. That incentivization stimulates the electric school bus market but raises the question of whether that growth can continue until costs come down significantly.

Conversely, propane school buses don’t need those subsidies, says Todd Mouw, executive vice president of Roush CleanTech, the propulsion technology supplier to school bus manufacturer Blue Bird. Savings total about $4,500 a year per bus, Mouw adds, and the typical payback is 18 to 24 months for a bus that will last 12 to 15 years.

Blue Bird propane school buses are on the road in 49 states, Mississippi being the exception, and in every province in Canada. The OEM has sold a total of over 23,000 propane school buses and 2,500 electric school buses since their introduction, says Albert Burleigh, vice president of North America Bus Sales for Blue Bird. (Other school bus OEMs, including Thomas Built Buses and IC Bus, also sold propane school buses, but no longer do.)

Burleigh adds that the OEM started building and selling propane school buses in 2008 and electric in 2018, and both fuel types are a growing percentage of the manufacturer’s business.

Diesel’s market share is expected to decrease. More school districts are moving away from diesel and switching to propane for cost savings and simpler maintenance.

Additionally, in 2027, EPA regulations will further restrict the maximum allowable nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions from 0.2 to 0.035. Making changes to bus aftertreatment will likely bring more complexity and cost.

“That concerns school districts because they’ve been through many emissions changes over the last 10 to 15 years,” Burleigh says. “Each time there’s a major change, generally, costs and maintenance are more than anticipated.”

Blue Bird’s propane school buses currently exceed the 2027 emissions requirement, at 0.02 NOx, without any aftertreatment equipment. The health and environmental benefits are also a plus for school district customers.

“That’s why we see more demand for that product, especially with that looming change,” Burleigh says.

Many school districts are looking at alternatives to diesel. Propane, with little difference in the upfront cost of the bus and more than $50,000 in savings over a 15-year life cycle, is a popular choice, Burleigh says.

That’s meaningful to school district business managers and transportation directors, who look for ways to cut costs.

Still, he adds, there are many customers who haven’t switched to propane yet: Of the more than 12,000 school districts in the United States, 1,100 include propane in their fleets.

“It’s a small piece of the overall business, but it’s growing every year,” Burleigh says. “Those 2027 emissions changes are going to be key to a lot of [school bus operators] making that conversion.”

Districts weigh in

Ron Stephens, transportation director for Wilkes County (Georgia) Schools, says that a combination of state and federal funding helped the district purchase 10 propane school buses, and later, the EPA’s Clean School Bus Program provided funds to replace 17 diesel buses with five electric and 12 propane school buses. That grant covered the $375,000 price tag for each of Wilkes County’s electric buses and provided another $20,000 for charging station equipment for each bus.

Stephens uses 22 propane and five electric buses for daily route service since those trips are shorter. The propane buses, he adds, are cheaper than diesel to fuel and maintain, but they get about half the mileage of the diesels: 5 miles per gallon (mpg) and around 9 mpg, respectively. Running 17 diesel buses for field trips, which typically require traveling over 100 miles round trip, can get expensive, he adds.

Wilkes County put its new electric buses into operation in October 2024, about one year after receiving them, due to delays with installing and obtaining some of the parts for the charging infrastructure. Three of the buses have been inoperable at least part of the time due to maintenance issues.

The two electric school buses that Stephens has in operation have run well, he says. They are quiet, the drivers love them, and they can travel about 100 miles on a full charge. That makes them a good fit for daily service on 20- to 30-mile routes with a chance to recharge midday.

Given a choice between the two fuel types, Stephens says his preference is for propane, mainly because of reliability.

“Sixty percent of our electric buses are not working,” he says. “I believe the technology will improve. They’re excellent buses when they work.”

Diana Mikelski, director of transportation at Township High School District 211 in Palatine, Illinois, agrees with Stephens that electric school buses may not be ready for significant deployment in many fleets just yet.

She points to the higher upfront price – typically $300,000 to $400,000 – for the buses.

“I can get two propane [buses] for that,” she says. “I can put [them] on the road right now and look at all the NOx I’m saving.”

Mikelski is also concerned about exceptionally cold temperatures reducing the range and timely maintenance.

“With propane, if I’m having an issue, my guys can pop the hood, take a look and fix it,” she explains. “I have to wait [several] weeks for [a technician] to come look at my electric bus because they’re shorthanded right now, and they’re [still] learning themselves. That’s the stuff I want to see solidified down the road, and I think that’s eight to 10 years out.”

Her district’s fleet includes 80 propane, 57 diesel and 25 gasoline school buses. Mikelski also ordered two more gasoline and nine more propane buses as the district’s transportation department phases out its diesel buses to eventually convert to an all-propane fleet.

Mikelski says refueling is the only issue she has encountered with the propane buses.

“You can’t go around every corner [like with gasoline and diesel stations],” she says.

Mikelski’s drivers use the alternative fueling station locator app from the U.S. Department of Energy to find refueling locations while driving for field trips, and drivers can refuel at a few locations where the department has set up accounts.

Northshore School District in Bothell, Washington, also runs a fleet with a few electric and propane school buses, which they obtained through the Clean School Bus Program. After the $600,000 grant kicked in, the district paid $200,000 for each of its three electric school buses, says Sabrina Warren, the district’s transportation manager.

Northshore had also ordered three more electric school buses through the program. They were set to arrive in August 2025. Due to the pause in funding, however, Northshore may need to cancel the order, depending on the cost.

One of the three electric buses that the district is operating had to be returned to the dealership because of an energy storage issue with one of the battery cells. The district is waiting to get the bill for repairs.

In addition to cost, Warren also has concerns about electric school buses charging during extended power outages.

“We had to shut down school for two days due to a windstorm that [downed] power lines,” she says. “How’s that going to be sustainable over time if you go with a whole electric fleet?”

Warren adds that although there are still many unknowns with electric buses, the school board wants to be proactive and run more clean-fueled and cost-efficient buses for the community.

“You also want to make sure you’re spending the taxpayer’s money the right way,” she says. “We believe in being greener, and propane costs less.”

Cypress (Texas) Fairbanks Independent School District began investing in a transition from an all-diesel fleet to a mix of fuel types in 2018 and has reaped the benefits ever since.

Today, the district’s fleet is composed of 447 propane, 250 diesel, 300 gasoline and 10 electric buses.

The district took delivery of its first 13 propane buses in 2018 and contracted on-site fueling, says Kayne Smith, Cypress-Fairbanks’ director of transportation. The buses operated well, and the lower cost of ownership drove the district to expand the propane portion of the fleet. It replaced about 400 diesel and gasoline school buses in one year. The district also invested in 18,000-gallon propane tanks and pumps at all six of its transportation centers to handle fueling in-house.

That paid off in 2022, when gasoline and diesel prices skyrocketed, but propane remained steady.

“One of the hardest things for a school district to budget for is fuel, because it can be volatile,” Smith says. “Because of our propane footprint, we were able to get through that fiscal year without asking for more money.”

Three years ago, the district varied its fuel mix further after receiving a grant from the Houston-Galveston Area Council for 10 electric school buses. This is the second school year that Cypress-Fairbanks operated the buses, with only minor issues related to integrating aftermarket products like air conditioning.

Cypress-Fairbanks and its energy provider started evaluating its facilities in 2019, before the buses arrived, for the required charging infrastructure without having to add switch gears or transformers. The district also built a new transportation center with plans for the infrastructure in place. Although the facility wasn’t ready when the buses arrived, the district identified places to add pedestals to support chargers and related equipment.

The buses have a range of 110 to 120 miles, and the average route is 60 to 70 miles a day.

“Those have also performed exceptionally well for us,” he says. “We now are very diverse, with electric, propane, gasoline and diesel.”

Propane’s opportunity

While it is smart for pupil transporters to take the opportunity to test the performance of a few electric school buses in their districts, Mouw says, funding availability is likely to change with the new presidential administration. That will add a hurdle to electric school bus commercialization.

Still, it is important to note that electric school bus sales will likely grow in states with substantial funding for them, such as California, New York and Massachusetts. While electric buses won’t overtake propane anytime soon, due to costs and more infrastructure complexities, the fuel could cut into propane market share a bit in those states.

Diesel, which has historically dominated the school bus fueling market, is still a formidable competitor, but regulatory changes that aim to further reduce NOx emissions will impact diesel aftertreatment technology costs and complexity. That may drive many pupil transporters to consider alternatives.

Still, Burleigh doesn’t anticipate an immediate propane sales spike, since many diesel customers aren’t ready to make the change. Some may even pre-buy in 2025 and 2026 before changes take effect, he says.