Trading versus hedging in propane futures

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, explains key concepts in propane futures.

Catch up on last week’s Trader’s Corner here: Far-out thoughts on buying propane

Let’s discuss the difference between trading and hedging in the propane industry.

I am an analyst in the propane industry. I don’t sell propane to consumers. Therefore, I can never be a propane hedger. I can only be a trader or speculator of propane. I could use my knowledge of the industry and the analysis of it to place bets on propane price movement, but the only way a position is beneficial to me is if prices move in the direction I predict, allowing me to financially benefit from the trade itself.

I can go long on propane futures, betting that prices will rise; I buy the commodity now expecting the price to increase so that I can sell it in the future at a profit.

Or I can short the commodity if I believe prices are going down. In that case, I commit to selling a specific quantity of the commodity on a certain date in the future at a certain price, but I don’t yet own the commodity or have a financial position on the commodity. When it’s time to fulfill my obligation, I expect to be able to buy the commodity needed at a lower price than what I committed to before the delivery date, thus profiting.

As a trader of propane, volatility would generally be my friend. It gives me opportunities to take positions and profit from them rather quickly. Time, on the other hand, is often the enemy of a trader. The further out one tries to predict prices, the more difficult it can be. Traders usually do better by taking positions for a relatively short duration and often by making numerous trades.

In short, traders only benefit when they make a profit on their position. They tend to make numerous trades. These trades are often short in duration. Volatility is usually their friend, and time is often their enemy.

In contrast, a business that is part of the supply chain, delivering propane to end-use consumers can be a hedger. A hedge is an action that is designed to counter the volatility in price of an underlying commodity.

Taking a hedge position should be beneficial even when the trade itself loses money. It is like insurance in that respect. It provides peace of mind even when a claim against the insurance is not necessary.

It also establishes risk within acceptable parameters. For example, the risk for insurance is the premium cost and the deductible. We accept that manageable risk (expense) rather than the risk that our business will be blown away by a tornado.

A propane retailer that hedges is generally transferring the risk of higher propane prices in the future by forfeiting the opportunity to buy supply for less in the future. A retailer must manage the risk of prices falling by establishing price protection or hedging when market conditions are favorable.

As we have discussed many times, we believe the risk to a propane retailer of being slightly overpriced in a low-cost pricing environment is far less than making the customers assume all of the risk of prices being higher.

If a retailer is slightly overpriced due to hedging in a low-cost and likely low-volume period, their consumers are far less likely to be jarred into exploring other options than when the retailer is passing on the full impact of high prices. A high-priced environment is generally associated with high demand, resulting in major bills being received by consumers. Such “shock” bills might drive them to look for other supply options or other energy sources. Hedging for a propane retailer is about managing that risk.

The purpose of a hedge is not to make money on the hedge. Rather, its purpose is to remove unknowns concerning the cost of a commodity to be sold. The profit for a hedger that is a commercial player delivering the commodity of propane to end-use customers is going to come from the margin made between the cost of supply and the sales price of the commodity, not from trading the commodity.

So even when a commercial player hedges propane and the hedge pays him, it should not be viewed that he made money on the hedge. It should be viewed that the hedge helped him make the desired profit margin on his primary business of selling propane to end users.

There are many actions that a propane retailer can take to make more profit on his part of the propane supply chain. For example, he can maintain his equipment properly, allowing it to last longer. He can hire good people who yield above-average productivity.

He can take actions to lower his cost of supply, such as establishing the cost of supply when market conditions have the cost of the commodity below normal or below average.

He can also take actions to allow him to charge more for the propane he delivers than other propane retailers. Things like customer service, reliability, predictability and flexibility can all come into play.

Propane retailers that use hedges such as swaps, options and pre-buys are primarily trying to accomplish three things:

- Protect customers from some of the impact of higher prices to increase the chances of retaining them.

- Provide predictable pricing that decreases uncertainty for the consumer.

- Increase profit on sales without increasing the sales price.

Note that we did not say, “Make money on trades by guessing correctly a commodity’s price movement.”

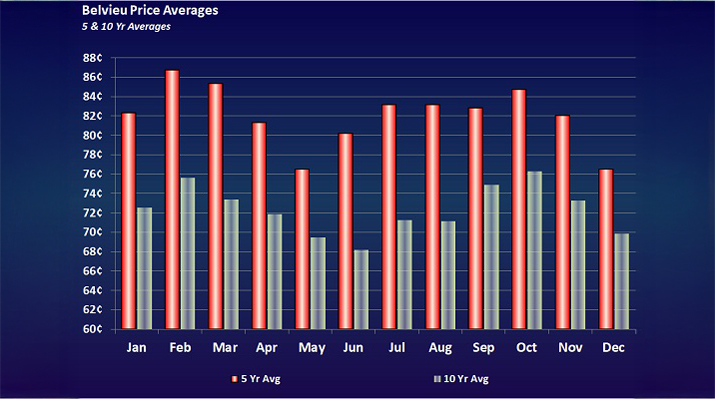

Hedgers often benefit from taking longer-term positions when the market has given them the opportunity to establish propane supply costs below certain benchmarks. For example, we often talk about establishing a cost of supply that is below the 10-year average for the price of propane. Doing so lowers the risk of falling prices.

As we discussed last week, the best opportunity is often to place a hedge for propane supplies that are not needed for two or three years out. Think of the benefit of that to the propane retailer. Over that two- or three-year span, almost everything will go up in price except the cost of supply.

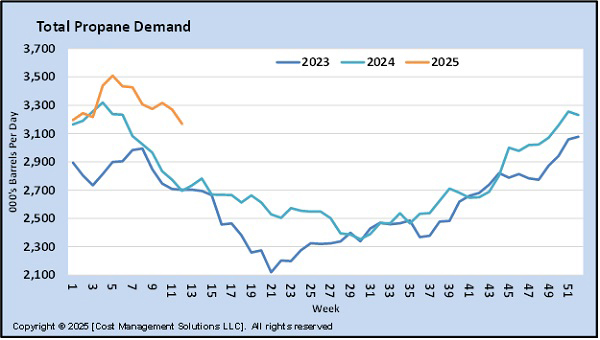

Volatility is not seen as a friend to members of a propane supply chain and thus not a friend to hedgers. In fact, a hedger is primarily trying to manage volatility. Whether a commercial player in a propane supply chain is drilling wells, fractionating natural gas liquids or delivering propane to consumers, price volatility always makes that entity’s job harder and decisions more difficult. All segments of a supply chain generally endeavor to reduce volatility. Hedging is often a part of that strategy. Turning the unknown future price of propane into a known helps with planning, marketing and decision-making.

A swap position is often two parties in a supply chain exchanging risk that helps both perform better and more predictably, thus helping the overall performance of the supply chain. As a propane retailer, when you hedge using a swap position, you are generally not privy to what entity is the ultimate counterparty, since you are going through a trading partner.

Traders that provide a swap market have relationships with parties all along the propane supply chain. Members on the upper end of the supply chain (such as producers) are hurt when propane prices fall. Members on the downstream end of a supply chain (such as retailers and consumers) are hurt when prices rise.

The swap allows two members of the supply chain to exchange risks, providing a benefit to both. For example, it helps a fractionator to know what they will receive for the propane they produce. Establishing the lowest price they will get for their production is beneficial. On the other hand, a propane retailer or consumer is hurt by higher propane prices. Establishing the highest price that will pay for supply is beneficial.

When a swap is done, a price called the strike price is established. Imagine there is no trader between the propane fractionator and the propane retailer. The swap position is done directly between the two. The fractionator decides to provide propane at a certain price in the future and the retailer agrees to buy at that price. If propane prices go down in the future, the fractionator is hurt. Establishing the lowest cost he will get for the propane through a swap agreement is beneficial. If prices go up, the retailer and consumers are hurt, so knowing the highest price they will pay benefits them.

The strike price of the swap is a predetermined value for the propane in the future that provides price certainty to both parties in the supply chain, thus benefiting both. Hedging turns unknowns into knowns for both sides of the swap transaction.

When a retailer writes a check because propane prices were lower than the strike price on the swap, the money, more times than not, is going to end up in the hands of some entity further up the propane supply chain from him. When he receives a check because propane prices were higher than the strike price on a swap, the money is likely coming from an entity further up the propane supply chain.

Hedging is not trading. It is managing risks associated with price volatility in a commodity. Volatility almost always hurts all members of a supply chain. Swaps are often allowing parties along the supply chain to exchange or offset risks. This aids the supply chain in being secure, efficient, predictable and reliable.

All charts courtesy of Cost Management Solutions

To subscribe to LP Gas’ weekly Trader’s Corner e-newsletter, click here.